Crystal Village

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", November 2002, page 3

A battered sign assured me! was at the Crystal Village. A thick chain dragged

on the ground between two posts and the sun glimmered on the sides of structures

that seemed to sprout among the weeds. There was no one about. Traffic roared by on Highway

3. The door of the church smacked methodically against its jamb like a lazy

horse swatting flies, and the wind made lonely music around the corners of a coal

shed. This was years ago, but I was already too late.

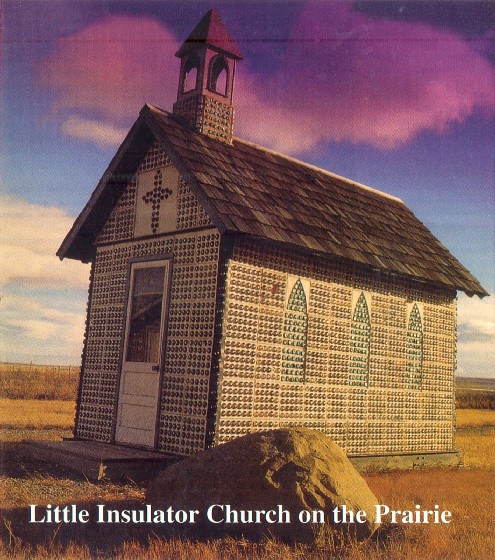

The Cover: CRYSTAL VISIONS

In 1970, about the time Pincher Creek resident

Boss Zoeteman retired, the phone company was changing technologies and no longer

required the clusters of glass insulators that topped telephone poles. What to

do with the thousands of now-obsolete glass beakers? Boss's first idea was to

make his granddaughter a doll house. But, never one to think small, Boss then

made what would today be called a paradigm shift: "To heck with the doll

house," he thought. "I'm going to create a city!"

Crystal Village

is a collection of 13 structures, including a school, church and trapper's

cabin, that Zoeteman meant to be a not-quite-life-size reproduction of Pearce,

Alberta, the town of his childhood. To achieve his goal, he collected more that

200,000 of the glass cups, which he then encased in cement blocks. The church,

his first and best building, is made up a hundreds of blocks and almost 6,000

insulators.

Alas, the Boss never did finish his project, for he died at the age

of 89. But the Village lives on, as part of Heritage Acres Museum, just a toss

of an insulator from the controversial Old Man River Dam. "He was an

incredible man," laughs his granddaughter, Mamie. "But he was

insane."

Article by Curtis Gillespie, WESTWORLD, Spring 1999 Photograph:

bix studios ltd.

|

Yet the trails between the buildings were not over grown, and hunks of coal

still hid the floorboards in the shed. Pieces of coloured chalk waited in the

pencil grooves of wooden desks in the schoolhouse. At the entrance to the church

I found a donation box with coins in it, and a guest book in which the last

entry was recorded by a family from Camrose, Alberta, nearly a year earlier.

Except for roofs and windows, the buildings were made completely from clear or

green glass insulators, but the insulators had been used differently in each structure. The schoolhouse and office building were constructed

of square wood frames, each frame holding twenty-five insulators. The framing

was cemented over, the office building painted white and the schoolhouse deep

red.

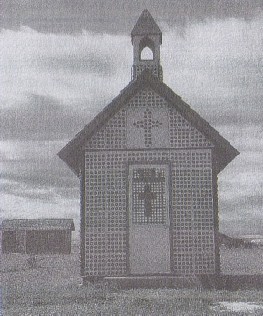

In the walls of the church, the builder had used as little mortar as

possible between insulators, so the inside was washed in green light. When I sat

in one of the handmade pews, the effect was like looking out from inside a vast

illuminated honeycomb.

The belfry of the glass-insulator church mimicked the

ubiquitous grain elevators of the prairie, some of which stood silently beyond

the northern end of the Crystal Village. No one was around them either. A cross

over the door identified the church as a place of worship, just as the golden

shafts of wheat served as a logo of farm commerce.

What had happened here after

the last visitors signed the book a year earlier? Why was the place deserted,

artifacts still lying about?

Bastien Zoetmann, nicknamed "Boss", had

died on December 14, 1989, his wife Burga told me. He had been a machinist by

trade, but Burga referred to him as "more the adventurer type, always doing

something different, jumping from one thing to the next."

Once he got the

notion sometime in the mid-1970s to build with insulators, there were evidently

no second thoughts. The thing had to be done. Zoetmann went around Alberta

collecting glass insulators from discarded telephone poles and used 5,642 of

them on his first project, a church for his Pincher Creek backyard. With 150,000

insulators remaining, he made a school, playhouse and office, the coal shed and

warehouse, and then realized he had the makings for an entire village.

But there

was still more to be done. He had exhausted his Alberta insulator sources, so he

acquired more of them from Holland, Denmark, Germany, Australia, Pakistan and

Japan. These were recycled into more buildings. By 1986 he had run out of yard.

Everything was transported to the new site, the property on the outskirts of

town near the junction of Highways 3 and 6.

Burga says her husband was an

incredible worker and seemingly endless reserves of energy. "He was at it

till nearly the end, building, landscaping, taking kids around." Zoetmann

had opened the village to visitors in 1987, and had arranged for school

to be conducted and church services to be held. Next came the buffalo and the

llama. No admission fee was charged, but he wouldn't turn down a donation.

The last

thing Zoetmann made was a taxi stand, so the invisible residents could wait for

invisible taxis. A few months before his death, he was still planning new

projects --- a castle and a large house for himself and Burga.

"It seemed to

me that he died suddenly," Burga told me. "But after he was gone, I discovered

he'd had cancer for a long time but had told no one, not even

me." After Zoetmann's death, the Crystal Village sat unattended and the

weeds did their work "I don't have the heart to even go out there."

Zoetmann was always disappointed by the reaction of locals to his work

"They didn't criticize him," Burga said, "They just sort of

ignored him." Not long after I talked to her, the Alberta Historical

Society arranged to have the buildings transferred to a park area near the site

of the Old Man River Dam. Burga was assured they would be surrounded by antique

farm machinery on a well-maintained plot of land. She considered this to be a

gesture of official recognition. "Isn't that the way it usually is? They

recognize you after you're dead."

Not long ago, I went out there to the Old

Man River Dam and had a look at the buildings. The well-maintained plot of land

is a featureless patch of the plains. No people, no friendly animals wander

between the buildings. Neither are there grain elevators for reference points or

traffic rushing by on Highway 3. The buildings just site there forlorn while the

wind blows relentlessly.

Submitted by James and 'Raine Mulvey, Cobourg, Ontario.

From the book, "Strange Site uncommon homes and gardens of the Pacific

northwest", by Jim Christy, Harbor Publishing, ISBN 1-55107-131-3

|